“Why did he do it?”

“He was told to do it.”

“Did he question it?”

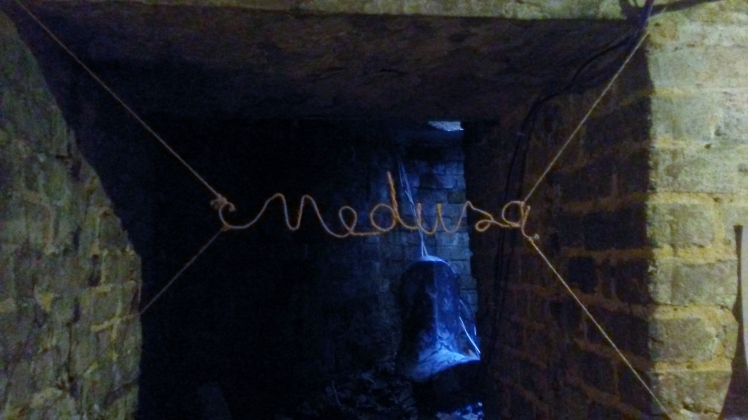

“Probably not.” – Medusa, The Crypt Gallery, 27 degrees

How do you remember the story of Medusa? Do you remember a myth about a scary monster with serptentine locks? A terrible woman who could kill you with a single stare? Something more? Something other?

That’s how I learned about her in primary school.

What we didn’t learn, of course, was the origin of this monster according to Greek mythology. If we stick to Ovid’s version, Medusa was once a priestess in Athena’s temple. Poseidon, god of the sea, seduced and raped her. Athena then placed a curse on Medusa, turning her hair into snakes and her stare into one of stone.

In other words, Medusa was tricked, assaulted and, if that wasn’t bad enough, stripped of her station as a high standing woman in society. All for something she did not do, want or ask for.

It’s depressing to see how such practice remains so common.

I just finished performing in “Medusa” by 27 degrees at the wonderfully atmospheric Crypt Gallery by King’s Cross. Something that was really nice about this version of Medusa was how focused it was on Medusa’s story. Not Athena’s. Not Poseidon’s. Not Perseus (who according to the myth, slayed her), but Medusa’s.

There’s a danger when it comes to talking about any sort of trauma a woman has experienced, or when it comes to discussing womanhood in general, and it is this – our language is so phallocentric that we are often unable to access the adequate words or phrases to express, demystify or decode our experiences. This is why, I think, new and specifically chosen words and expressions are so important. It’s so important to be aware of whose narrative viewpoint you are telling the story from.

Once we manage to change the language, we can finally begin to decolonise ourselves

said Chusi, a good friend of mine and also a member of 27 degrees. She was speaking specifically of Latin America, but I think this is a pretty applicable quote to what I’m talking about here.

But this performance used Medusa as a lens to ask the question: ‘What does it take for a woman to be considered a monster in the 21st Century?’ In other words, Medusa as the key to opening the doors into a more contemporary inquiry. It is, in my opinion, a powerful show and a very necessary one.

It’s also important to be aware of the current climate. Of the ‘zeigeist’, and, just as importantly, of your own emotional space so that your social consciousness can be used to enrich a performance.

On the final show day, I was a little unwise with my morning. I’m usually quite good in the mornings and do what is necessary for me to feel whole and at rest. (I’m not perfect at it, but not awful either!) Usually I try to pray first thing in the morning. This really sets my heart right before God. It puts me in a place of peace and faith. Unfortunately, I didn’t do that on the final show day. I spent the first hour upon waking scrolling through social media, and then I spent another hour catching up on Dr. Christine Blasey Ford’s testimony and then, after that, watching Brett Kavanaugh’s defending himself.

Obviously, this left me in a really shaky, sort of nauseous and even anxious way. And I totally carried that with me on my journey to the performance venue. Fortunately, I managed then to pray and do some emotional preparation before. I was able to find a balance in which I was emotionally stable yet could still bring a sense of sobriety, that sense of duty to perform for the women who have been assaulted and then discarded. Assaulted and then disbelieved. Assaulted and then…well, does anything else need to follow? That’s brutal enough.

I’m sure most people are aware of Medusa’s origin, but I really wasn’t so I thought it would be interesting to write about. It’s interesting how her narrative makes her out to be a monster when actually, Poseidon with all his power and authority, was the true monster in this story. It’s interesting how the narrative frames Perseus as the hero.

In 1975, French writer Hélène Cixous wrote an essay entitled, ‘The Laugh of Medusa’, in which she talks about language as a means of entrapment, and suggests how women might reframe language structures to escape from systematic oppression. She emphasises the importance of storytelling, of bodies and of individual narratives.

“Our Medusa is finally free.” – Medusa, The Crypt Gallery, 27 degrees

So perhaps, when all is said and done, it is much, much more interesting to consider how we might write our own narratives. Greek mythology gave us Medusa but how we choose to remember her, and every single woman we know today who comes forward about abuse, is up to us.